Effects Of Housing Crisis, Homelessness Permeate State Of Living In The Bay Area

SAN FRANCISCO (KPIX 5) -- The housing crisis has crept its way into every corner of life in California.

You see it on the street if you walk to work in the San Francisco or if you're slogging through a super-commute to the South Bay. It's personal--what could be more personal than your home? Or lack thereof?

The housing crisis has its hands on our collective throats and we're faced with a choice: fight or flight.

"I have no idea, on my income I have no idea where I would go," Linda Owens said.

Owens lives on a fixed income and her landlord is raising the rent, which could force her to leave the Bay Area entirely.

"I know rents are high out there, I can't afford to go out and pay $1800-1900 a month for a one bedroom," Owens said.

Parents like Paul Boehm are embracing solutions in their backyard. He built an ADU for his daughter so she doesn't have to move to Sacramento.

"She's a teacher, her husband is a counselor, so they're not in the tech industry and they could not afford the kind of housing prices in the Bay Area that most people pay," Boehm said.

So how did we get here - where the average price of a home in San Francisco is $1.4 million and two bedrooms are renting for $4,500 a month? In San Jose, the average price of a home is $991,000 and two bedrooms rent for $2,936 a month, while in Oakland the average price of a home is $732,000 and two bedrooms go for $3,024 a month.

Homeownership in California is the lowest it's been since 1950 and homelessness numbers are skyrocketing statewide. Point in time homeless counts indicate 8,022 homeless live in Alameda County, a 42.5% increase since 2017. Santa Clara County is home to 9,706 homeless, a 31% increase since 2017. 8,011 homeless live in San Francisco, a 6.8% increase in two years. 1,512 homeless live in San Mateo County a 20% increase in two years, and 2,295 homeless live in Contra Costa county a 42.8% increase since 2017.

Every year California spends more money on the problem. Gov. Gavin Newsom allocated $2 billion to combat the housing crisis this year.

"I think the housing crisis has been so hard to solve because there are so many entrenched interests in seeing the status quo remain," said David Garcia, Policy Director for the University of California, Berkeley Terner Center for Housing Innovation.

"It really boils down to the fact that we have not produced enough housing to keep up with our population growth and our job growth in our state," Garcia said.

In many ways the Bay Area is a victim of its own success. Largely driven by tech, the region is home to nearly 4.1 million jobs. Just after the recession in 2009 there were 3.3 million jobs, that's a 23% spike in 10 years adding just under 773,000 jobs.

Parallel to that job growth is a failure to build. Supply and demand does deserve a lot of the blame. The state is on pace to build fewer than 100,000 homes in 2019. State research indicates California needs to build 180,000 homes a year to pull itself out of this mess. Governor Newsom's goal is more than double that, he wants to build 500,000 homes a year to have 3.5 million new homes by 2025.

"Every year that goes by is another year we're falling short of that goal so I would say it's not looking good," Garcia said.

The cost of construction is also a major factor. The Terner Center released a study this summer that found fees do deter development. In particular, impact fees - which pay for local services like parks and schools and vary widely from city to city. Developers can expect to pay $3.5 million in fees to build a multi-family project in Oakland, $7.5 million in fees for the same project in Fremont and $1.7 million for the same project in Sacramento.

"It's hard to have a conversation about how to reform impact fees without looking at the underlying fees of our property tax system," Garcia said.

This brings us to what used to be considered the third rail of California politics, Proposition 13. Gov. Jerry Brown called it "a sacred doctrine never to be questioned" Prop 13 passed in 1978, it caps property taxes at 2% increases each year, so some homeowners and businesses are paying property taxes that haven't changed much in decades despite substantial increases in home values. As a result, cities have raised fees to build to make up for that lost revenue. A ballot measure to amend what businesses pay might be headed for the ballot in 2020.

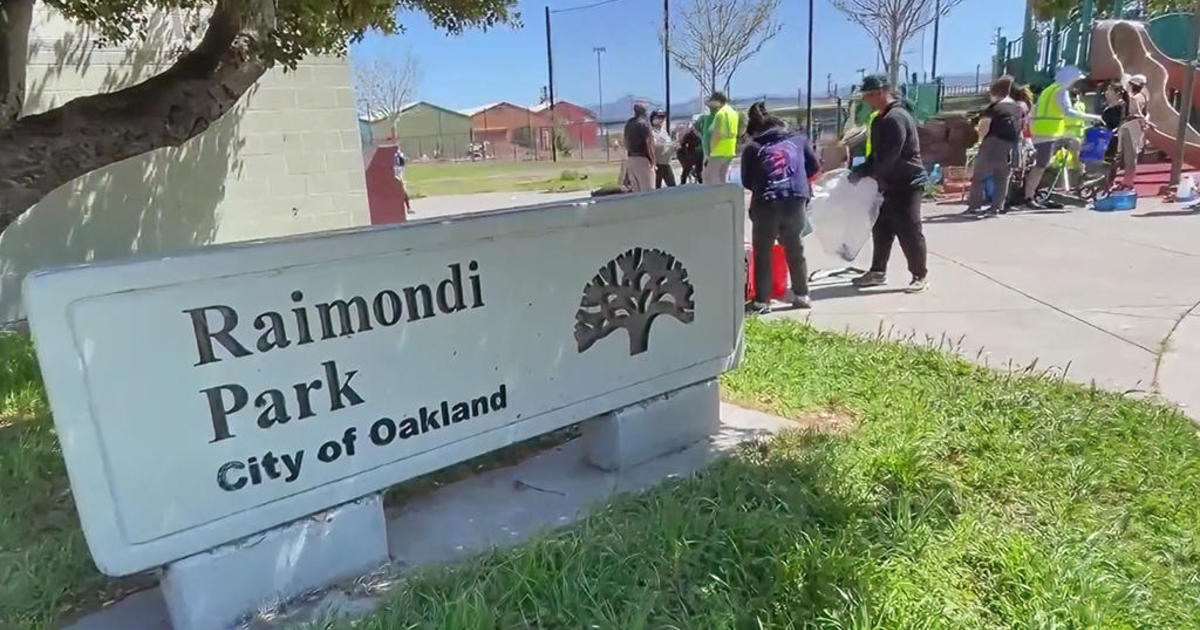

Web Extra: Oakland Mayor Libby Schaaf

During a comprehensive interview about the housing crisis Oakland Mayor Libby Schaaf told KPIX she supports some changes to Prop 13 for commercial buildings. We sat down with all three mayors of the Bay Area's largest cities for the launch of Project Home. Each of them list housing and homelessness are their top priorities.

"I think a generation or two from now they'll be asking what did you do about it (the housing crisis) and if we can't answer that question in a way that satisfies our own conscience and the conscience of the next generation I think history will not regard us well," San Jose Mayor Sam Liccardo said.

Web Extra: San Jose Mayor Sam Liccardo

"I want people to recognize that housing is a human right, people die without adequate shelter," Schaaf said.

"As someone who grew up poor and lived around a lot of people who have struggled, it's hard to see the poverty play itself out in such an extreme way on our streets," San Francisco Mayor London Breed said.

Each mayor has hard to reach goals in place for housing and homelessness. Liccardo wants to see 10,000 new homes built by 2022, San Jose still needs to build 8,900 more units to attain that goal. Breed wants 1,000 new shelter beds in San Francisco by 2020 and is on track to have 817 built by March, and Schaaf wants 17,000 new homes by 2024. Oakland has built 10,000 new homes since that goal was established in 2016.

Web Extra: San Francisco Mayor London Breed

All three mayors say we need to be building more housing, and we need to communicate to our communities that more housing doesn't necessarily change the soul of the city.

"A lot of communities are focused on preserving their character rather than realizing we're all being harmed by the shortage of housing," Schaaf said.

They agree tech hasn't done enough collectively to combat the crisis, and that needs to change, "we've been complicit in the notion that if we expand tech campuses all will be well and someone else will worry about the housing," Liccardo said.

They want to change the way we talk about homelessness.

"We've got to agree as a Bay Area community that our homeless are ours they're part of our community," Liccardo said.

Don't doubt that housing hits home for them, too; none more so than Breed who grew up in public housing in San Francisco and says she's unapologetic about the need to bring people indoors.

"I spend time in the Tenderloin and I run into a lot of people I grew up with and they need help, its heartbreaking," Breed said.

Time will tell if these three can rally support needed for a regional approach they think is needed to solve this crisis.

On the way we'll hold them accountable, and explore solutions that indicate, maybe the American Dream isn't dead, it just looks different. The stakes here are high. The fears are real. The middle and working class are disappearing. It's a corner we've backed ourselves into and it's time to find our way home.